Al-‘Auja and Za‘atra July 14, 2023: Margaret Olin’s blog Touching Photographs

Sometimes trying to find Abu Isma‘il in the hills and wadis of Al-‘Auja is, well, like looking for a goat in a desert. The Rashaidi Bedouins of ‘Auja have names for every rocky hill and wadi, names that no one else knows, that appear on no map; and Abu Isma‘il usually has trouble telling me on the phone where he is with his flock. Finally, not long after dawn, we climb a few hills until we sight him, with his red keffiyeh, surrounded by sheep, sheep dogs, and one very young donkey.

A happy reunion, as always. He’s in a good mood. “Problems this week?” I ask. “Life,” he says, “is never lacking in problems.” “What happened?” “Soldiers came a few days ago, dispersed the sheep, and drove us away.” He seems not unduly disturbed. Even as we are chatting on the hilltop, Omer, the arch-settler who has generated much of the agony of Auja, calls him on the phone. A courtesy call, as it were. But I can hear the threat just by listening to Abu Isma‘il’s responses. Afterwards, Abu Isma‘il says, “He warned me not to come close to his farm. He told us to go away.”

In the distance, we see another Palestinian herd, pretty close to the road that is the arbitrary boundary the army has declared; whoever crosses it is likely to be punished, beaten, driven away, maybe arrested. I say to Abu Isma‘il: “Omer is now going to call out the soldiers, just wait.” Later it turns out that the herd belongs to Ibrahim, one of the shepherds from Muarrajat just to the west of Auja. My prophecy is fulfilled within minutes. We get an emergency call from Ibrahim, via Yigal in Jerusalem. Soldiers have come. They threatened him. Scattered the herd. Drove them away. He’s scared. But I missed the call. Too late. By the time we reach where we thought he was, he has disappeared with his sheep. When I finally reach him by phone, he is already safely home, al-hamdu lillah.

In short, a perfectly normal morning in Auja. By 8:00, the temperature is well over 40 degrees Centigrade. Too hot even for the sheep. But Abu Isma‘il, in his Zorba mode, is overjoyed to see us– Lexie, Peg, Maureen Chun, on her first visit to the Valley, and me. He jokes with Isma‘il, his son, who appears riding a handsome white donkey. Abu Isma‘il says this fine donkey has absconded from his true master.

Today is a good day. In the evening, there will be an ‘urs, a wedding. They are bringing the bride from the Jiftlik in the far north of the Valley; she is to marry one of Abu Isma‘il’s nephews. There will be songs and much dancing, even a mutrib, a professional singer, whom they’ve called down from somewhere in the hills. The bride will be carried by her family to her bridegroom’s home. Before all that, in the afternoon, the women will start cooking a feast. They’ll slaughter a sheep. It will be busy today, but none of this stops Abu Isma‘il from bringing us home to Duyuk for strong super-sweet Bedouin tea and a breakfast of freshly baked pitta and olive oil and za’atar and tomatoes and fried potatoes. Umm Isma‘il serves us, sits with us; she is hungry to learn a few English words, like the name for what Peg has brought with her to the shaded breakfast porch with its pomegranate and olive trees. It’s ridiculous, says Umm Isma‘il, that any human language could have a word like “back-pack.” She rolls the syllables on her tongue, plays with them: bakpak, bakpak, bakpak.

We join Guy and a slender file of activists at Za‘atra in the central West Bank, at Tapuach Junction, adjacent to the famous village of Hawara. Palestinians in this area are surrounded by some of the most brutal, crazed Israeli settlers, including those who burned down the houses of Hawara, torched many cars, beat up whoever they could find, and killed one man, from Za‘atra, in March. (They also took time out, amidst the flames in the village, to pray the evening prayer, Ma‘ariv, I suppose checking in with their implacable god.)

So for an hour or so we stand at the junction displaying our signs: “Palestinian Lives Matter.” “The Occupation kills.” In big Arabic letters, Hebrew too. We’re here to give moral support. Many dozens of Palestinian cars pass us, many honk in delight, smile at us, thank us. Best of all are the children who can read the signs and understand them, who wave their fingers with the victory sign. Then there are the settlers with their usual, impoverished curses and threats, not worth repeating.

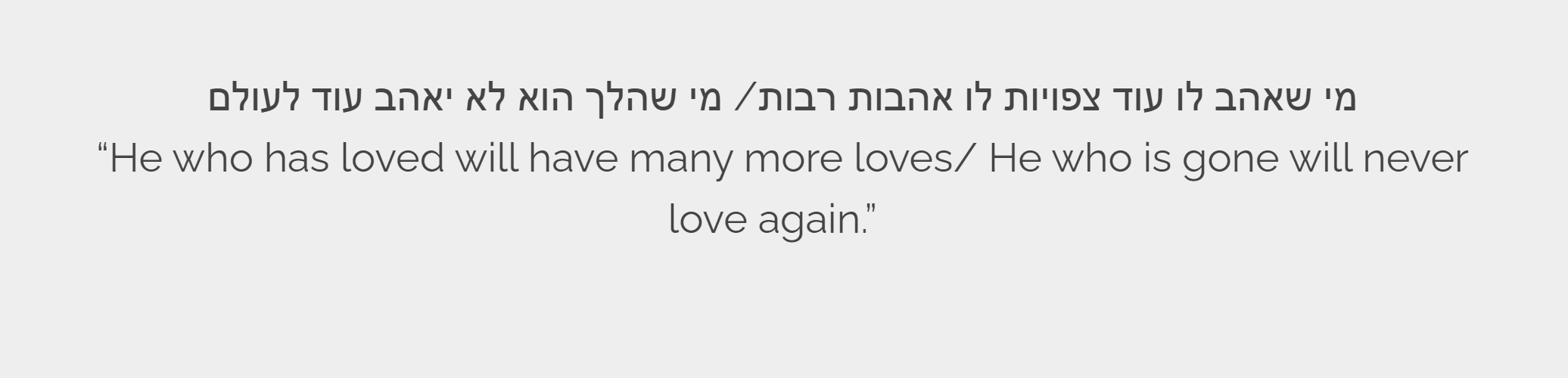

One sign, different from all the others, catches my eye. Yarden Levital has created it and is holding it up high. It reads:

מי שכבש הוא לא יאהב עוד לעולם.

Freely translated: “He who conquers/occupies will never love again.” Sometimes you learn something new and lovely at a demonstration. The line goes back to a well-known song composed by Didi Manussy (the music is by Yohanan Zarai) in 1967, after the war. Like many popular songs in Israel, this one is about war, heroic death, and, above all, lamentation for the dead in battle. But the original line reads:

You have to know the intertext to get the full force of the altered wording on the sign. The occupier occupies the place of the dead. Did the latter die for nothing? Maybe not then. But look at Israel today. The occupier is killing love.

On the reverse of the sign, there is another altered quotation, this time from a poem by Haim Guri from the 1948 war. The original poem , another lament, says:

The brotherhood in question is the solidarity among soldiers at war. In this rendition, the relevant verse begins just after the 2:00 mark. But the sign says:

הצייתנות נשאנוך בלי מלים: “Following orders: we carried you out/ without words.”

Let no one say that the Hebrew words of the past have lost their resonance. Decades of bitterness, irony, and malice have only deepened it. Following orders, in silence: the army disease, the sickness of an entire country.

A young settler, waiting at the bus stop nearby, is also intrigued by this sign or by the activist who holds it. He comes over to tease, or to bug, or to sneer at Yarden. “Where can I buy the teeshirt you are wearing?” [It reads: “There is no democracy with Occupation.”] Yarden: “You can buy one for 50 shekels.” The settler backs off. Yarden says to him: “It’s expensive to be a leftist.”

One more philological excursus. Standing next to me in the midday fire of the sun is Lexie, a young, erudite student and teacher of the Talmud. We chat about goodness, wisdom, how to study Talmud, and the deadly mutation in the mind that the modern ethno-state unfailingly produces. Lexie is a true activist, and a good friend to Abu Isma‘il. She asks me if I know what the ancient sages have said about the verse

But the sages say the word chamushim, חמושים, is linked to chamesh, חמש, the number 5. So what is the verse telling us? Only a fifth of the people of Israel actually came out of Egypt; the other four-fifths were so at home there that they couldn’t bring themselves to become free. Thus in the Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael. Another voice says that only one in 50, or one in 500, was able to free themselves.

Maybe it’s always like that. It’s so much easier to enslave oneself to the infinite cruelty of the occupation, to follow orders, to believe or pretend to believe the lies that issue every hour from the prime minister and his thugs, to swallow the poison of hate, to die for some pathetic Netanyahu or other in yet another foolish war, than it is to own that slight margin of inner freedom that makes one human.

I look around at the activists with their signs. Some I know from years in the field. Each one of them one in five hundred. Why else would they be here today?

This piece was written by David Schulman and photographed by Margaret Olin and posted on Margaret Olin’s blog Touching Photographs. It can be accessed here along with other interesting stories.